Sunday, 28 February 2016

My Star Wars Theory of Japanese Literature

The Japanese influence on the original Star Wars films is so well known that it hardly needs recapping. It's long established that George Lucas took many elements of the plot of the 1958 Akira Kurosawa film Hidden Fortress - about a couple of bickering peasants escorting a princess across enemy territory - and transformed it into a sci-fi spectacular, set in a distant galaxy, a long, long time ago, Kurosawa's peasants became C3PO and R2D2, samurai swords turned into lightsabres and the code of bushido somehow became subsumed into 'The Force'.

Almost as interesting as the films themselves is the story of how the films came about in the first place and the myriad of influences and chance happenings that shaped them. George Lucas set out to make a Flash Gordon-esque sci-fi film and was famously influenced by such writings on mythology as Joseph Campbell's 'The Hero with a Thousand Faces'. His drafts of plots for the original film went through a dizzying array of rewrites with at one stage Luke having many brothers and a father supposed to appear in the film. At one point the film boasted the lengthy title, 'Adventures of Luke Starkiller, as taken from the Journal of the Whills'.

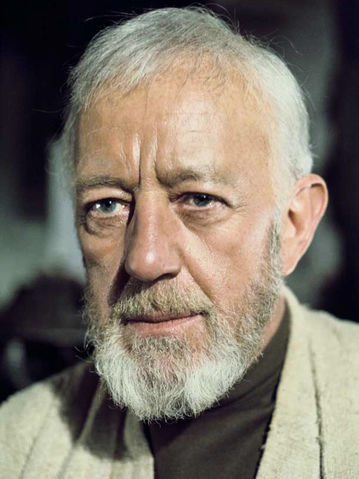

Yet for me the most fascinating moment in the original Star Wars is when Obi-Wan Kenobi after half-heartedly engaging in a lightsabre duel with his nemesis (and former pupil) Darth Vader allows himself to be struck down. 'Allows himself' are the operative words. The standard interpretation is that Obi-Wan sacrifices himself in order to let Luke, Princess Leia, Han Solo et al escape as they blast off in the Millennium Falcon from the imperial mothership.

Such an interpretation seems inadequate: Obi-Wan's final action appears far more calculating and significant. Pitted against Darth Vader, who could fail to notice how Obi-Wan deliberately looks across at Luke and slightly smiles, then willingly offers himself up for death? This is not someone who is resigned to oblivion, but who is intent on becoming reborn, more powerful than ever, in the mind of his young apprentice Luke.

The plot device of Obi-Wan dying in the middle of Star Wars IV was apparently a last minute re-write: originally Obi-Wan was supposed to not only survive until the end of the film, but also continue to be a major character in the subsequent two films. Sources disagree as to whether the plot change was a last minute idea of Lucas that displeased actor Alec Guinness or (perhaps more likely) a plot change suggested by Guinness himself to minimalize his commitments in the subsequent films after he had already tired of a film which would go on to make him extremely rich.

However it came about, like many last minute plot changes, it's crucial to the meaning of the film as a whole.

In the first half of Star Wars, we see some early examples of Obi Wan's adept use of 'mind control'. When he and Luke are stopped by Imperial troops, Obi Wan easily plants words into the mouth of the soldier-clone, allowing the party to continue on their way. Storm troopers are easy to manipulate, but when Obi Wan tries the same trick again in a raucous bar with a surly outlaw attempting to pick a fight with Luke, it has no effect, requiring Obi Wan to strike him down with his trusty lightsabre.

Obi Wan therefore clearly appreciates that to gain the upper hand on an opponent, sometimes you can use simple psychology, other times you need to resort to physical force. But to truly gain lifelong control of someone's psyche, you have to be prepared to lay down your own life. A lot of very calculated thought has gone into that life-parting, little smile.

This aspect of the film always connects in my mind to the most famous Japanese novel of the modern age.

Natsume Soseki's Kokoro (the Japanese word for spiritual 'heart' or 'mind'), written in 1914, is an overwhelmingly popular work in Japan, that has been recently serialized in its entirety in the leading national Asahi newspaper to commemorate its centennial anniversary. The novel was translated into English by Edwin McClellan in 1956 and a new translation by Meredith McKinney published by Penguin Classics in 2010.

The novel tells of the spell cast on a young narrator by a slightly older figure he refers to as 'sensei', the Japanese term for a respected teacher or elder(still from the 1955 Kon Ichikawa film below, narrator left and 'sensei' right). The character 'sensei' it turns out is harbouring a deep secret from his past which he reveals by means of a long letter to the narrator which comprises the second half of the book. It turns out that 'sensei' has been haunted by the suicide of his close friend K as a consequence of a love triangle back when they were students. The suicide has had the effect of K effectively seizing control of Sensei's heart ('kokoro') from beyond the grave.

Sensei understands the power of suicide to affect the heart of the person left behind and carefully bides his time looking for someone on whom to exert the same influence. Sensei indeed waits until the narrator has returned home to nurse his dying father before revealing his devastating secret and announcing his own suicide. The novel ends with the narrator fleeing his own father's deathbed as he rushes back to the place where Sensei lived. Sensei manages through a carefully staged suicide to create a bond which supersedes even the bond between father and son.

I've no idea whether George Lucas read Kokoro or watched Ichikawa's film, though Kurosawa, whom Lucas both admired and supported, was, like many Japanese, a great fan of Soseki. Kurosawa's 1990 film Dreams for example was a straightforward homage to Soseki's 1908 work Ten Dreams.

The aggressive nature of Sensei's suicide has tended to be overlooked by generations of fans in Japan, just as Obi-Wan's self-perpetuating suicide in Star Wars is mistakenly seen by legions of fans as noble self-sacrifice.

Famously, Alec Guinness when told by a fan that he had seen Star Wars over a hundred times is said to have granted an autograph provided he didn't watch it again. Guinness, a classically trained Shakespearean actor, might not have felt the film worth as many repeat viewings as the Bard's great plays. Yet ironically it is Guinness' character whose influence resonates endlessly beyond the grave. As with Kokoro's Sensei however the true nature of Obi-wan's final action is strangely missed by viewers determined to believe in impulsive self-sacrifice rather than shrewdly calculated psychological manipulation.

Wednesday, 24 February 2016

What's the Most Re-readable Work in Japanese Literature?

In a Guardian article last year, author Stephen Marche coined the word 'centireading' in discussing the merits of reading a work of literature 100 times. This set me thinking: if you were to choose a classic of Japanese Literature worthy of being re-read 100 times which one would it be?

There's certainly plenty of Japanese books I'd love to go back and re-read two or three times: 'The Tale of Heike' or Junichiro Tanizaki's 'Makioka Sisters' or plenty of things by Edogawa Ranpo all spring to mind. But 100 times? For me, if it was even 5 times, that would immediately rule out both exhausting monster books like 'The Tale of Genji' and contemporary modern novels.

Indeed I think there could only be one answer: 'Botchan', the 1906 novel by Natsume Soseki. I'm confident that I could read 'Botchan' 100 times and never tire of it. Indeed, I suspect I would get something new out of it on every reading. Let me briefly explain the main reasons why.

Firstly, sheer readability. If you are going to read something 100 times, you don't want something that's difficult to get through, full of longeurs and in general need of an edit. You need a work where every word counts, that has an unstoppable driving momentum. Botchan is a novel that picks you up in the first sentence and after taking you on an exhilerating ride drops you off neatly at the end, leaving you wanting to do it all over again. And again. And again.

Botchan is like this because of the particular way it was written. Soseki wrote the novel in a period of less than two weeks in his 'spare time' while he was still holding down teaching jobs at three educational institutions and returning to a home with four small children. The following year Soseki would give up his teaching posts and become a professional novelist for the Asahi newspaper, but in 1906 works of genius were surging forth out of him like magnificent, irrepressible volcanic eruptions.

Reason Two: Botchan is (to paraphrase Woody Allen in 'Annie Hall') a 'full meal'. Were you going to read a book so many times, what genre would you wish it to be? Comedy? Tragedy? Satire? Memoir? Elegy? Botchan is all these genres combined.

Most people know it as one of the most brilliant comedies in Japanese literature and indeed the comic set pieces - Botchan being baffled by the impenetrable dialect of the locals for example and responding with his own Tokyoite beranme-cho; or his battling against grasshoppers left in his bed by mischievous students - offer some of the most laugh-out-loud moments in the nation's literature.

What people don't generally realize however is that elements of tragedy are just as prevalent in Botchan: the central story is of Botchan's love for the elderly house servant, Kiyo, a mother-like figure whom he has left behind in Tokyo. At the end of the novel, Botchan's very identity crumbles and his brief period of carefree abandon is over.

But Botchan contains so much, much more. The novel is a satire on the divisions which had arisen in Japanese society after the Meiji Restoration between those factions previously aligned to the shogunate and those who had overthrown the old order. The novel is also a satire on Soseki's own snooty colleagues at Tokyo Imperial University, whom he lampoons in the form of nicknames ascribed to the teachers at the provincial Middle School at which Botchan arrives.

Matsuyama and nearby Dogo Onsen, where Soseki taught as a young man in 1895-6, is generally thought to be where the novel is set, creating a tourist bonanza which continues to this day. Yet what most people don't realize is that many different aspects of Soseki's own biography are subtly entwined in the novel. Botchan's longing for Kiyo in distant Tokyo for example is actually a reflection of Soseki's experiences in Britain in 1900-1902, when he desperately longed for his wife - also known as Kiyo - back home in Japan.

Which takes us to Reason Three: inexhaustability. If you are going to read a book 100 times, it needs not just to be compulsively readable and a 'full meal', it also needs to be one infinite in its capacity for offering up new insights, where the tiniest details seem redolent with meaning. What is the significance of the tree whose chestnuts were 'more important than life itself' to Botchan as a child? Why does the arch-villain Redshirt always wear a red shirt? Why should it be so ironic that Botchan and his ally, 'The Porcupine', style themselves as 'Divine Avengers' for their final attack on Redshirt?

Botchan is ultimately the story of the modern world itself. Botchan is a proud scion of the samurai and looks down with lofty disdain at backward country bumpkins, without realizing that it is the very process of modernization and westernization sweeping away the past that has been responsible for creating a development gap between Tokyo and the provinces. Botchan speaks to a universal condition: we are proud of our sophistication and modernity and yet we still cling to the image of a less brutal, warmer-hearted past.

In truth, Botchan is the only Japanese classic which I think I could happily read 100 times. Short of being washed up on a South Pacific island that may never happen, but if you haven't done so already, I earnestly entreat you to read it at least once.

There's certainly plenty of Japanese books I'd love to go back and re-read two or three times: 'The Tale of Heike' or Junichiro Tanizaki's 'Makioka Sisters' or plenty of things by Edogawa Ranpo all spring to mind. But 100 times? For me, if it was even 5 times, that would immediately rule out both exhausting monster books like 'The Tale of Genji' and contemporary modern novels.

Indeed I think there could only be one answer: 'Botchan', the 1906 novel by Natsume Soseki. I'm confident that I could read 'Botchan' 100 times and never tire of it. Indeed, I suspect I would get something new out of it on every reading. Let me briefly explain the main reasons why.

Firstly, sheer readability. If you are going to read something 100 times, you don't want something that's difficult to get through, full of longeurs and in general need of an edit. You need a work where every word counts, that has an unstoppable driving momentum. Botchan is a novel that picks you up in the first sentence and after taking you on an exhilerating ride drops you off neatly at the end, leaving you wanting to do it all over again. And again. And again.

Botchan is like this because of the particular way it was written. Soseki wrote the novel in a period of less than two weeks in his 'spare time' while he was still holding down teaching jobs at three educational institutions and returning to a home with four small children. The following year Soseki would give up his teaching posts and become a professional novelist for the Asahi newspaper, but in 1906 works of genius were surging forth out of him like magnificent, irrepressible volcanic eruptions.

Reason Two: Botchan is (to paraphrase Woody Allen in 'Annie Hall') a 'full meal'. Were you going to read a book so many times, what genre would you wish it to be? Comedy? Tragedy? Satire? Memoir? Elegy? Botchan is all these genres combined.

Most people know it as one of the most brilliant comedies in Japanese literature and indeed the comic set pieces - Botchan being baffled by the impenetrable dialect of the locals for example and responding with his own Tokyoite beranme-cho; or his battling against grasshoppers left in his bed by mischievous students - offer some of the most laugh-out-loud moments in the nation's literature.

What people don't generally realize however is that elements of tragedy are just as prevalent in Botchan: the central story is of Botchan's love for the elderly house servant, Kiyo, a mother-like figure whom he has left behind in Tokyo. At the end of the novel, Botchan's very identity crumbles and his brief period of carefree abandon is over.

But Botchan contains so much, much more. The novel is a satire on the divisions which had arisen in Japanese society after the Meiji Restoration between those factions previously aligned to the shogunate and those who had overthrown the old order. The novel is also a satire on Soseki's own snooty colleagues at Tokyo Imperial University, whom he lampoons in the form of nicknames ascribed to the teachers at the provincial Middle School at which Botchan arrives.

Matsuyama and nearby Dogo Onsen, where Soseki taught as a young man in 1895-6, is generally thought to be where the novel is set, creating a tourist bonanza which continues to this day. Yet what most people don't realize is that many different aspects of Soseki's own biography are subtly entwined in the novel. Botchan's longing for Kiyo in distant Tokyo for example is actually a reflection of Soseki's experiences in Britain in 1900-1902, when he desperately longed for his wife - also known as Kiyo - back home in Japan.

Which takes us to Reason Three: inexhaustability. If you are going to read a book 100 times, it needs not just to be compulsively readable and a 'full meal', it also needs to be one infinite in its capacity for offering up new insights, where the tiniest details seem redolent with meaning. What is the significance of the tree whose chestnuts were 'more important than life itself' to Botchan as a child? Why does the arch-villain Redshirt always wear a red shirt? Why should it be so ironic that Botchan and his ally, 'The Porcupine', style themselves as 'Divine Avengers' for their final attack on Redshirt?

Botchan is ultimately the story of the modern world itself. Botchan is a proud scion of the samurai and looks down with lofty disdain at backward country bumpkins, without realizing that it is the very process of modernization and westernization sweeping away the past that has been responsible for creating a development gap between Tokyo and the provinces. Botchan speaks to a universal condition: we are proud of our sophistication and modernity and yet we still cling to the image of a less brutal, warmer-hearted past.

In truth, Botchan is the only Japanese classic which I think I could happily read 100 times. Short of being washed up on a South Pacific island that may never happen, but if you haven't done so already, I earnestly entreat you to read it at least once.

Friday, 19 February 2016

Five Things You Need To Know About Cecil Rhodes

(Warning: this piece contains a distressing image).

I've been following with some interest a debate which has raged over the last few months in the UK about the unlikely subject of the fate of a statue. The statue in question is of Cecil Rhodes (pictured above), arch British imperialist of the late nineteenth century, and endower of the Rhodes Scholarships at Oriel College, Oxford, allowing generations of outstanding students from overseas to study at Oxford. Beneficiaries of the Rhodes scholarships have included a president of the US (Bill Clinton), and numerous Prime Ministers of Pakistan, Canada and Australia.

Last year a successful campaign to remove a large statue of Rhodes (pictured left) from the University of Cape Town spread to Oxford itself. The campaign 'Rhodes Must Fall' declared that Rhodes was a racist who had wrought untold damage on the native peoples of Africa and that the college should, belatedly, refund its ill-gotten benefaction to the people that Rhodes stole from in the first place. The campaign also sought to highlight inequality of representation for ethnic minority groups at Oxford and to decolonize the curricula. Oriel College took the campaign seriously and announced it would conduct a review process to see whether its own statue should be removed. This in turn prompted an uproar from those who felt that this was political correctness gone mad and many newspaper inches were filled with heated debate on the subject, with a former prime minister of Australia (Tony Abbott) and a former white president of South Africa (F W de Klerk), and perhaps more surprisingly the black former chair of the UK's Equality and Human Rights Commission Trevor Phillips, all weighing in to say that the statue of Rhodes should stay in place, and that attempts to remove it were, according to Philipps, 'witless and wrong-headed'.

Other commentators pointed out however that consigning statues to oblivion - such as those of Queen Victoria in India or those of Communist leaders in eastern Europe - were all part of natural historical evolution. The 'should he stay or should he go' debate finally received a full airing at the Oxford Union in January where by 245 votes to 212 it was carried that the statue should indeed fall. By this time however disgruntled members of Oriel College had already threatened to cancel tens of millions of pounds in intended donations and seeing what a disastrous impact the debate was having on the college's reputation (indeed on Oxford's reputation as a whole), it was quickly announced that the statue would after all remain in place and the provost of the college responsible for the PR fiasco was besieged with calls to resign. As a sop to the 'Rhodes Must Fall' faction, it was announced that although the statue (hard to spot below, but high above the central arch of the college entrance) would stay, a plaque providing 'context' to Rhodes' questionable life would be installed. We wait to see what exactly that 'context' will be.

One of the many curiosities of this furious, much-publicized debate is that hardly anyone in Britain today has any idea who Cecil Rhodes was and what exactly he was responsible for. Most people tend to vaguely think of him as a personification of the worst excesses of nineteenth century British imperialism, with the row descending into a partition between those who think that more reparations and apologies are needed for imperial exploitation and those who think that enough is enough and that endlessly trying to judge people of the past by today's sensitivities and standards is self-serving and futile.

The one point of agreement between the 'Rhodes Must Stay' and 'Rhodes Must Fall' factions was that Rhodes' actions - his imperial plundering of vast swathes of southern Africa, including modern-day Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana and South Africa and his firm assumption of white racial superiority - were unacceptable in today's enlightened age and were at the heart of the problem. The only question is how do we today judge people who lived in an age when moral assumptions were completely different. The 'Rhodes Must Fall' faction indeed argued that even in Rhodes' own lifetime his actions were judged by many to be greed-driven and immoral.

I want to argue here that both the 'Rhodes Must Fall' and the 'Rhodes Must Stay' factions are equally deluded - indeed utterly blind to reality - in their assumption that the assessment of Rhodes should consist of a morally enlightened present looking back on a morally challenged past. Indeed what is really important about Rhodes, and yet what is ignored, is the insight his extraordinary life story brings to us about the follies of the present age, indeed to what is a universal constant of human history.

Cecil Rhodes caused pointless misery to millions of people. This was not primarily caused by his 'racism', indeed he probably caused just as much disaster to white people as to any other variety (should such things be the subject of your interest). His influence was calamitous because he had a gargantuan flaw. But he was also a brilliant man, whom I in many ways admire. Polarizing debates demand that we cast people as straightforward 'heroes' or 'villains'. Rhodes was actually both hero and villain, but the important thing is to critically discern where exactly it was that a man like Rhodes went wrong and why.

Before coming to the calamitous flaw, I'd like to tell you first of four reasons why I really admire Cecil Rhodes. It all comes down to this: Cecil Rhodes was a truly brilliant businessman. He understood (reason one) that success in life involves calculated risk and technological innovation. If you wish to understand that principle, there is no better place to go than Kimberley in South Africa, home to the 'Big Hole' (pictured below), in the 1870s and 1880s the biggest diamond mine in the world.

Cecil Rhodes was the sickly son of a cleric in England who suffered his first serious heart attack at the age of 19 and was predicted to have 6 months left to live. Sent to South Africa as a young man of 17 he thought he might as well get a move on in life and when a diamond rush broke out in Kimberley headed out to join a multitude of other prospectors. What happened in Kimberley is a wonderful case study of entrepeneurship (aka capitalism) in action. Rhodes steadily bought out all the prospectors' strips and amalgamated them into his own holdings. He did in truth not exactly start from rags - he is known to have been given £2000 (worth about £200,000 today) by an aunt - so he certainly had a major head start. But he also had the courage to buy the land and take the risk: the prospectors who sold to him (and who were subsequently hired to dig for him) must have thought they were taking a fool's money. But Rhodes, not they, understood the golden rule of business/ capitalism that it rewards those who are prepared to invest in risky enterprises. Rhodes followed up the speculative purchases by introducing the latest technology to help make the mines more efficient. By the mid 1880s, when Rhodes was in his early thirties, he could boast an annual income of £50,000 (about £5 million in today's money).

Reason Two: Rhodes understood the importance of branding. You and your product are not the same, indeed you can create a separate brand identity by the simplest of methods. In Rhodes' case, his company De Beers was named after the Afrikaner farm on which diamonds had first been found. By this simple means he created a separate identity for all business activities: indeed for generations afterwards right up to the present day, people buying a piece of jewelry from De Beers often have no idea they are buying a product of Rhodes' former company.

Reason Three: Rhodes grasped the importance of understanding, adapting to and manipulating your market. Rhodes realized that the market for his diamonds - engagement rings in the West - was entirely governed by the number of couples in the West getting betrothed every year. Flooding the market with diamonds would simply mean that the price of diamonds would collapse so he shrewdly rationed supply.

Reason Four: Almost impossibly Rhodes somehow seemed to combine being a student at Oxford with being a young entrepreneur in South Africa. Later on he combined being a politician in South Africa with being a big society presence in the UK. He was I suppose what the long-established Afrikaner settlers in South Africa used to crudely refer to as 'salt-dicks', men who never wholly gave themselves to Africa but so straddled South Africa and Europe that their genitals were supposed to have dipped into the briny sea. For the Afrikaners it was a term of abuse, but it seems inspirational how Rhodes back in the 19th century managed to achieve so much on two opposite sides of the world (famous image of Rhodes bestriding Africa below).

Which leads me to the fifth thing you need to know about Cecil Rhodes, where it all went disastrously wrong. This can I think be summed up quite simply: Rhodes believed that the same principles with which he had achieved success in business could be equally applied in politics. As a young man of 27, Rhodes became a member of parliament of Cape Colony (most of current South Africa) and rose up from there to be Prime Minister by the age of 37. Business and politics for Rhodes went hand in hand. As a politician he dreamt of extending the British Empire in one continuous block through the whole of Africa from Cairo to the Cape and successfully schemed to add present day Botswana and Zimbabwe to the British Empire, famously signing numerous concessions with tribal chiefs which ceded rights to areas the size of modern African countries for a relative pittance in return.

Rhodes was here acting on a modus operandi of the British Empire which had been in evidence for generations, stretching back to the nefarious activities of the East India Company in Bengal and many other places. Servants of commerce and governors were encouraged with a nod and a wink from the government in London to grab what they could, then administer it from their own profits, and if any outrages occurred, the government back home could then loftily announce that Her Majesty's Government was now taking direct control to restore order.

In the case of Rhodes, the whole of southern Africa appeared like the diamond mine at Kimberley, something which he desired to have monopolistic control over. When vast gold deposits were discovered in the Afrikaner republic of Transvaal, it drove Rhodes to distraction that he (and by extension the Empire) did not have control of it. Here he employed his second principle of business - what I would characterize as the 'De Beers feint' - in which he attempted to use a front for his political ambitions. Famously in 1895 he backed the disastrous Jameson Raid in which his close friend Leander Starr Jameson and 600 horsemen, mostly policemen from the Matabeleland Mounted Police, attempted to ride into the Transvaal and seize control for Rhodes. Instead Jameson and his accomplices were captured and the scandal forced the end of Rhodes' political career. But behind the scenes he still would not give up and four years later engineered the Boer War by encouraging the British Government to provoke war on the Transvaal and the Orange Republic on the utterly specious grounds that they would not grant voting rights to Uitlanders (foreign workers in the Tranvaal, whom Rhodes hoped would effect a coup d'etat on his behalf).

The Boer War would last for three long years and pointlessly sent 21,000 British soldiers to their deaths. It caused misery and deprivation for the British, white Afrikaner and black African population of South Africa and eventually saw 27,000 white Afrikaner women and children, and a slightly lower but comparable number of black Africans, perish in concentration camps introduced for the first time by the British that became the scandal of Europe (horrific image of Lizzie Van Zyl below who died in Bloemfontein Concentration Camp). Ironically, Rhodes himself - a major architect of the conflict - died at the end of it, from his long-standing heart complaint, at the age of 48.

The lesson I take from Rhodes' life is the utter devastation that can be unleashed when a hugely talented man of business is let loose upon the international political stage believing that the same principles that guide one in business apply to politics. This is something which is still at the very heart of world affairs today.

Take for example the disastrous US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. It fascinates me how many similarities there are between that calamity and what transpired in southern Africa in 1899. In his desire to get his hands on the gold of the Transvaal, Rhodes and his associates concocted a narrative of outrage about an oppressive Afrikaner government suppressing democratic rights. The war that broke out as a result devastated southern Africa. In the case of Iraq, a desire to assume control of Iraqi oil led to the US and UK talking up a terrifying narrative of 'weapons of mass destruction' mixed in with emphasis on genocidal atrocities. Famously, the Americans having conquered Iraq, had no plan whatsoever on how to govern the country. It was confidently assumed that the influx of Western capitalism - a gold rush of American companies eager to grasp the mineral wealth of Iraq - would inevitably lead to a glorious age of democracy. It was, and is, a truly Rhodesian delusion.

If there is a lesson to be learnt from the life of Cecil Rhodes then it is that capitalism should learn humility and know its limits. It should work within political frameworks not attempt to drive political ambitions, where its influence is often catastrophic. For me, this is the important, universal 'context' which should be written loud and clear in any assessment of the life and achievements of Cecil Rhodes, not some deluded trumpeting of our supposed moral superiority over our Victorian ancestors.

(For more information on the shocking image of Lizzie Van Zyl, click here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lizzie_van_Zyl)

Friday, 12 February 2016

Becky, Taeko Kono and Japan's 'Kawaii' Culture

When I was at the Daiwa Foundation in London last week I met for the first time a Facebook friend called Lucy North, who had come up specially from Hastings for the event. Lucy is one of those fascinating people that you feel you need a couple of evenings of conversation to sufficiently navigate your way around: I discovered that she had been raised in Malaysia, had specialized in Japanese Studies at Cambridge, done a PhD in Japanese Literature at Harvard, lived for eight years in the US and another thirteen in Tokyo...

She handed me a copy of a collection of short stories by a writer called Taeko Kono (pictured below) which she had translated some 20 years ago. 'Was I familiar with Kono's work?', she asked, telling me she was passionate about her writings. The book had the distinctly unusual (and to be honest pretty off-putting) title, 'Toddler-Hunting'. It's probably not a book I would I have picked up if left to my own devices, but since it had been expressly handed to me I made it my business to start reading it on the train home the next evening.

I've already had my share of 'unsettling' Japanese books in the last few months, having written a review (forthcoming next month) of Ryu Murakami's 'Tokyo Decadence', a collection of short stories featuring explicit sado-masochistic sex, and Akiyuki Nosaka's 'The Whale that Fell in Love with a Submarine', in which all manner of gruesome wartime horrors are described (albeit in a beautiful fairy tale format). But I would have to say that by far the most disturbing, stimulating read I've had in a long time is 'Toddler-Hunting', a collection of short stories from the 1960s all featuring female protagonists by one of the most significant, though still relatively obscure, female writers of postwar Japan.

Taeko Kono - who died in January last year at the age of 88 - freely admitted the influence of the writings of Junichiro Tanizaki, who explored in his writings the taboo of perverted desires. Kono's female protagonists too seethe with neuroses and barely suppressed hatreds and desires. Many of them are sexually masochistic: one character despises pre-pubescent girls and wishes to exert power over pre-pubescent boys. Where the stories gain their power and traction however is the way in which Kono describes such complexes as being entirely normalized. Where Ryu Murakami's writes of sado-masochism in graphic, sensationalistic terms, as usually the realm of sex workers, for Kono this is something which is coolly dropped into the narrative almost as an aside.

The stories are more disturbing than anything Tanizaki ever penned because the 'perversions' are not overtly flaunted in front of us, but stoically, internally borne by her female characters and often revealed with biting satire and black humour. There is a strong sense that these are universal conditions that must arise when the characters are forced to live under psychologically oppressive cultural constraints. If a woman in 1960s Japan felt forced to marry and live a sequestered life in support of her husband, as a child-like dependent, and pressured to fulfill the biological destiny of becoming a mother, why would her daily psychological frustration not transmute and vent itself in some perverted form, whether taking pleasure in self-harm or in a visceral hatred for infants of her own gender?

A recurring theme of Kono is that of the 'false parent', in which it either transpires that someone imagined as blood relative turns out to be a stranger or that a step parent entrusted with the child's care secretly hates them but is agonizingly bound to them. In one of her most disturbing stories, 'Snow', the female protagonist is the illegitimate child of her father with a mistress and her upbringing is forcibly imposed upon the father's wife as a stepmother. Overcome with hysteria, the stepmother, Medusa-like, murders her own infant child of the same age by leaving her out to die in the snow. You very strongly sense in all these stories that Kono judges Japan itself as a 'false parent' to its psychologically oppressed female population. seeking to smother their natural identity and replace it with something which is fake and imposed.

At the same time as reading Kono's trenchant if occasionally torturous stories, I've been following the ongoing fallout from the sudden fall from grace of Japanese TV Tarento 'Becky' (pictured top and below) - a pretty, vivacious 31-year-old who was until recently a ubiquitous presence on Japanese television and advertising. An idol and role model to Japanese youth, Becky suddenly found herself frozen out of the Japanese television firmament once a Line conversation supposedly sent to a 27-year-old married pop singer Enon Kawatani implying an illicit affair came to light. (It should be noted the general circumstances were bizarre, with Kawatani's own marriage last summer being made public at the same time.)

There's been quite a brouhaha particularly from the Western media about how this incident illustrates the vice-like grip of managers in the Japanese entertainment world (Becky's own management team even apparently suggested she be dropped from her ten regular TV programmes) and of sexist double standards: Kawatani, who was the alleged 'adulterer' - it all sounds very 19th century - has not had his career similarly affected.

I sympathize with the sentiment but I don't personally think this analysis actually gets to the heart of the matter. Indeed I think there is something far more symptomatic about Japanese expectations of women in general revealed.

Becky was the epitome of Japanese 'kawaii' (meaning 'cute' in a child-like way) culture. I watched her on a show over the Christmas break which starred the seven male members of a popular band called Third Generation J Soul Brothers in a Christmas special. The 'boys' - all in their twenties and thirties - had each been asked to come up with the perfect Christmas gift for a girlfriend. Becky and another female presenter were brought in to judge and rank their choices.

One member of the band chose a gift which he said would be delivered as a surprise to the hotel room he was staying in with his girlfriend. Becky, with her beautiful manga-esque wide eyes, primly chided him for thinking he could take his girlfriend to a hotel room so quickly, even though it's a tradition in Japan for courting couples to spend Christmas eve in a hotel together. Instead, two members of the band chose as their Christmas gifts tickets to Tokyo Disneyland. Becky and the other presenter were in agreement that this was the most 'romantic' gift.

In the West, Disneyland is a place that you generally think of taking pre-teen children and if a man in his thirties were to suggest taking a 31-year-old woman there on a date, it's likely he would be thought either slightly strange or studiously ironic. But in Japan's 'kawaii' culture, where girls are encouraged to remain eternally child-like, a trip to Disneyland is considered not just unobjectionable, but an ideal romantic day out.

The show was of course a piece of artifice from start to finish. We can comfortably assume that the male members of a rock band with a colossal female fan base have a steady stream of young girls at hand to afford pleasure in their hotel rooms. In this fantasy scenario however, Becky was appearing not just as a participant but as the very arbiter of 'kawaii'. It's pretty inevitable therefore that if one is found out to be actually far more worldly - a pretty normal adult woman in fact - then your TV persona is going to be difficult to maintain.

For me though, the Becky incident is not about the methodology of TV management or indeed of sexism and double standards on television. It's more an extraordinarily vivid representation of a usually hidden pressure in Japan for women to play along with the child-like, naive role. Failure to do so, to be one's natural self - an intelligent, independent, occasionally risk-taking woman - threatens, as in Kono's story 'Snow', the female being pushed out to perish in the metaphorical snow while a more compliant substitute takes your place.

I don't want to sound too down on 'kawaii' culture, which of course has its charms, and I don't want to suggest that replacing it with cynical, in-your-face Western attitudes would represent a step forward. But you can't help thinking that for many intelligent Japanese women being trapped in a culture dominated by constant demands for 'kawaii' must solicit a long, intense psychological scream.

What can be done about it? To really empathetically connect with the experience of women in modern Japan, to hear their true inner voices, not the fabricated constraints of 'cutishness' you have I think to turn to the great Japanese female writers and listen carefully to what they have to say. At the top of any reading list in this area I would now place this very oddly named book, a cri de coeur for women to be treated as complex adults not children: 'Toddler-Hunting'.

Saturday, 6 February 2016

Japan Times Articles on Lafcadio Hearn

I recently wrote a couple of review articles connected to Irish author Lafcadio Hearn. Here's a link to my review of Insect Literature (pictured at top), the new and beautifully illustrated collection of writings by Hearn on insects from Swan River Press, opening up to us a fascinating 'other world' right in front of our eyes.

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2016/01/23/books/insect-literature/

And here's a link to my mini review of 'A Fantastic Journey: The Life and Literature of Lafcadio Hearn' (pictured below), the classic biography of Hearn by Paul Murray.

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2016/01/02/books/book-reviews/fantastic-journey-life-literature-lafcadio-hearn/

Insect Literature shows to us in full I think Hearn's wonderful sensibility combined with a terrific gothic imagination. But I also can't resist quoting here the magnificent piece of scatological invective which I refer to in my short review of Paul Murray's biography.

Here's Lafcadio in Yokohama in 1890 writing a letter to the owner of 'Harper's Magazine' telling him exactly what he thinks of him and his magazine and returning all contracts:

'(you are) liars - and losers of MSS - employers of lying clerks and hypocritical, thieving editors, and artists whose artistic ability consists in farting sixty-seven times to the minute - scallywags, scoundrels, swindlers, sons of bitches.

Pisspots-with-the-handles-broken-off-and-the-bottom-knocked-out ignoramuses with the souls of slime composed of seventeen different kinds of shit, know by these presents there exists human beings who do not care a c**tful of cold piss for 'their own interests' if it is indeed to their own interests to deal with liars, scoundrels, thieves and sons of bitches...All the money of all the States of America and Mexico could not induce (me) to contribute one line to your infernally vulgar beastly goodey's-Lady's-Book-Magazine, you miserable beggarly buggerly cowardly rascally boorish brutal sons of bitches. Please understand that your resentment has for me less than the value of a bottled fart, and your bank account less consequence than a wooden shithouse struck by lightning.'

(From 'A Fantastic Journey: The Life and Literature of Lafcadio Hearn' by Paul Murray (1993), p.133)

Friday, 5 February 2016

What Would Octavio Paz Think of Donald Trump?

For some months now it seems as though my newsfeed here in the UK has been swamped by articles on the various candidates in the US Presidential election. The election appears to have been going on for longer than the American Civil War and prompted such large amounts of partisan animus from my American friends that my heart sinks to think that the dratted thing has only just reached the first state caucus stage.

The smart move when referring to the politics of another country is obviously to be studiously complimentary to all parties, in the manner of Stephen Fry who ingratiated himself to his American hosts last time round by telling them that Barack Obama and John McCain were both 'quite remarkable men'. I will therefore refrain from expressing any sense of despair at the prospect of some of the current candidates actually winning.

My attention though was taken by reading an analysis of maverick Donald Trump's enduring popularity. Voters are turning to him it seems because in a world of increasing uncertainty and challenges to American hegemony, they desire to see a 'strongman' in the White House. All Trump's policy proposals - from imposing tariff barriers against Chinese imports to keeping out Muslims and (perhaps most notoriously) sending back illegal Mexican immigrants and building a wall on the border 'which the Mexicans would pay for' - apparently merely bolsters the desired 'strongman' image. The odd misogynistic comment apparently doesn't do any harm either.

This set me thinking about the classic 1948 book The Labyrinth of Solitude (revised in the 1960s and 1970s) in which Octavio Paz attempted to delve into the idiosyncrasies of the Mexican character and the distinctiveness of Mexican culture. Why was it, he asked, that Mexican culture was so different to that of its rich neighbour, the United States? Indeed why was there such a vast economic and social divide between these two nations?

Paz saw Mexicans as an essentially retiring people who were afraid to show their true characters and lived by a series of masks presented to the outer world. It was only on occasions such as the fiesta when the Mexican could show his or her true self. The rest of the time, Paz argued, men aspired to machismo - to being strong silent types - so their vulnerabilities would not be seen. Women were treated as passive and expected to be hidden away and long-suffering about the trials of life.

In Paz’s analysis, there were two strains to Mexico’s politics. The first was a pyramid structure with an Aztec-style ruler at the top, whose power was impersonal, priestly and institutional. The embodiment of this in the Mexico of the time, Paz said, was the president, whose power was enormous, but impersonal. The other strain was the caudillo, the regional boss or warlord, which belonged to the Hispano-Arabic tradition. The caudillo belonged to no caste and was not selected by the establishment, Paz remarked, but appeared at times of crisis and confusion and ruled until the storm blew over.

Paz (pictured left) did not say so explicitly but in comparison of the 'pyramid structure' of Mexican society, he presumably thought of US society as being a squashed diamond with a wide seam of affluent and contented middle class voters tapering down to a relatively small working class and tapering up to a rich elite. He also seemed to think of the US president as the embodiment of a more consensual politics, a primus inter pares figure.

With the manifest failure of 'trickle down economics' and the explosive growth in wealth differentials over the last 60 years however, US society these days resembles a teardrop diamond, heavy-bottomed and with an untouchable political class, funded by the super-rich, sitting at the very top. Into this world of uncertainty and confusion, Donald Trump appears as the classic Paz-style 'caudillo', the strongman come to reassert certainty and order.

I'm sure Mexico itself is considerably more sophisticated these days than when Paz described it in the post-war decades. Yet it's interesting that if 'caudillo' Trump were to triumph, US politics would more closely resemble the patterns that Paz described in Mexico. One rather suspects that society too might become pyramid shaped as wealth steadily trickled upwards.

At Donald Trump's campaign rallies, in order to taunt Canadian born Republican rival Ted Cruz, they apparently like to blare out the old Bruce Springsteen song 'Born in the USA' indifferent to the irony that the song does not celebrate but rather excoriates the US. There's a certain irony that if Trump's policies were ever actually realized - with every Mexican illegal immigrant sent home and a large wall erected along the border - the America quarantined on the other side under its strongman president would be more classically 'Mexican' in character than it had ever been in its history before.

Thursday, 4 February 2016

Natsume Soseki, Ireland's Easter Rising and China's Cold War

In a few weeks time, on April 24, Ireland will commemorate the centennial anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, when over 1000 Irish patriots launched a surprise attack on strategic buildings in Dublin and other locations in Ireland and proclaimed an Irish Republic. The nationalists managed to hold out for a week before, faced with overwhelming British military superiority, surrendering. The Rising left over 450 people (mostly civilians) dead and thousands injured. The British government - in the midst of its life-and-death struggle with the Central Powers in the First World War - responded to the uprising by arresting 3500 people and executing 16 of the Rising's ringleaders.

The traditional interpretation of the Rising is that although it failed, it served to both galvanize and radicalize Irish nationalism, particularly because the British executed the ringleaders turning public opinion in their favour. Violent resistance to British rule would immediately erupt again in the Irish War of Independence of 1919-21 leading to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. Since that time the 1916 Rising has been enshrined as part of the very foundation myth of modern Ireland, as witnessed by copies of the 1916 Declaration of Independence (image at top) hanging proudly in many Irish pubs across the world.

I generally like to celebrate Ireland from the safe remove of distant lands rather then drench myself in its history. Yet it's curious how in our inter-connected world, going to the farthest reaches of the planet can offer you new insights on the part of the world you (or in my case, my forebears) first came from and I want to write here a little bit about how delving into the literature of Japan can offer a surprising insight into subjects like the 1916 Irish Rising despite on the face of it having no obvious connection.

The first and long-standing Irish leader Eamon de Valera did a very successful job in recreating Ireland as he saw it - agrarian, spartan, obeisant to the Catholic Church. This was supposed to have been Ireland in its natural state, having shook off the oppression of the British. It comes as a shock however to learn of all the other multitudinous possibilities that Ireland may have grasped back in the 1920s had the visions of other freedom-loving aspirations come to the fore. Many wanted Ireland not to be a backwater, but to be a modern Utopia, a beacon of progressive ideals to the rest of the world. Indeed it's only really now, a hundred years after the 1916 Rising, that this 'other Ireland' is finally beginning to be realized. Endless waves of sexual abuse scandals involving Catholic Brothers and Priests has forever undermined the power of the Church in Ireland and opened up a new liberal space. The national plebiscite in favour of changing the constitution to grant gay marriage was a turning point and would doubtless have de Valera spinning in his grave.

At the same time as this turning away from conservative nationalism however, there has also been a questioning of the 1916 Rising itself. Two years ago, former Taoiseach (prime minister) John Bruton dared to speak the unspeakable when he asked in a speech if the 1916 Rising was actually necessary. After all - and this is a key point - the Home Rule for Ireland bill had already passed all three stages of the British Parliament and was on the brink of being enacted when the First World War broke out, causing it to be postponed until the end of the War. Was it really worth the 450 lives lost and thousands injured in 'The Rising', not to mention the descent of Ireland into years of internecine civil war for years afterwards, when self-government could have been delivered peacefully?

Bruton (pictured right) was careful to note that he did not doubt the 'sincerity' of the men of 1916, though some historians have been overtly critical of the agenda of those ringleaders who would be later effectively canonized as 'martyrs'. I won't pretend I know enough about the background of the 1916 rebels and the dizzying complexity of all the Irish nationalist groups of those days to pass comment, but I do think there is a very important element of the debate - indeed of our understanding of the First World War as a whole - which is ignored and it's at this point that I think turning to the unlikely source of Japanese literature is extremely instructive.

At the beginning of 1916, the great Japanese author Natsume Soseki penned a series of pieces in the Asahi newspaper called Tentoroku (which means 'New Year Chronicle'). Japan had a relatively minor role in the First World War, allied to the Entente Powers and mopping up some of Germany's colonies in the Far East. Generally speaking though it seems remarkable how little Soseki - the most famous author in the country and the star writer for the nation's leading newspaper - actually ever mentions the war. For Soseki it just seemed to be like business as usual and he continued serializing novels until his unexpected death in December 1916.

In his 'New Year Chronicle', Soseki refers to how another 'big war' has broken out (Japan had fought its own 'big war' with Russia in 1904-5) and talks about what seems like a relatively minor point, that Britain was about to start introducing conscription. Soseki goes on to say how unexpectedly strong Germany had proved to be in the conflict and that to combat that strength Britain was having to abandon her libertarian traditions and adopt German methods. In that sense, Soseki remarks, Germany was winning the war.

The standard interpretation is that Soseki (pictured below) simply did not understand how utterly momentous the First World War was, and perhaps this is understandable given how far away Japan was from the main theatre of conflict, how relatively slight was her involvement and of course that Soseki died midway through the war.

That interpretation is mistaken. In fact Soseki's observations are strikingly acute. It's curious that in the plethora of commemorations currently taking place throughout the world to remember the First World War, this key issue of 'conscription' is hardly ever mentioned and yet it is absolutely essential in understanding a watershed moment in the history of the British Empire.

It's almost completely forgotten today that until 1916, Britain was the only combatant in the First World War not to rely on conscript armies. Indeed in its entire history, the British Empire - defended by its all-powerful navy - had never had recourse to conscription, proudly maintaining a tradition that it could rely on volunteers to willingly die in the name of King and Country. Whatever the reality of the situation, the British Empire presented itself as a sort of kindly, patrician gentleman's club, inspired by civilization and high-minded ideals, in which 'primitive peoples' were looked after rather than coerced or exploited. It crucially relied on the members of the empire also sharing this vision of freedom under the flag and the common good.

Conscription changed all of that forever. It was one thing for Australian prime minister Andrew Fisher to declare in September 1914 when asked if Australia would back Britain in the war that they would 'defend her to our last man and our last shilling', but that relied on a vision of Australians volunteering their services and lives for the empire (recruitment poster below). When in 1916, the Australian government under pressure from the British attempted to introduce conscription, it was narrowly rejected by national plebiscite (and rejected again by a greater margin in 1917). Australia remembers today as part of its foundation the blood sacrifice of Gallipoli, but arguably just as significant was the attempt to impose conscription. Nothing quite focusses the mind on your relationship with 'The Motherland' as the thought as having to die for them whether you wish to serve or not.

The same was exactly true in Canada, where attempts to introduce conscription in 1917 met with riots and forceful protests from the Francophone Quebecois community.

In Ireland, the conscription issue was crucial. It was one thing to be told that the implementation of the Home Rule bill was to be put on a back-burner until the end of the war, but the British Government then attempted to link the promised implementation with Irish accession to conscription. Of course, from the British Government's point of view, sending out in 1914 a professional army of 100,000 men to meet a German conscript army of 5 million, it was quickly obvious that large-scale recruitment of men was desperately needed. Many in Ireland - as in Canada and Australia and throughout the British Empire - freely and bravely volunteered to fight in the war (or else were lured into it by thoughts of 'adventure' and 'mateship'). But for Irish nationalists, who may have been content to sit out the war and wait for the implementation of Home Rule, the spectre of imminent conscription in 1916 was unquestionably the event that concentrated minds on a 'Rising'.

Indeed, rather than predominantly see the British government's execution of The Rising's ringleaders as the key event that radicalized Irish nationalism, I would argue that it was actually the proposed introduction of conscription in 1916 and a further attempt in 1918 (anti-conscription rally right), when Britain was even more seriously short of men and staggering following the success of Ludendorff's 1918 Spring Offensive, that pushed Ireland into urgent demands for independence.

Soseki's analysis of what was happening in the war in 1916, far from being a concentration on a minor topic, acutely analyzes something that would presage the entire downfall of the British Empire. Never again would the Empire be able to operate under the mystique that it was about freedom and volunteers, rather than land and coercion. Indeed it's significant that 1916 was also the year of the Sykes-Picot agreement, in which a covert agreement was drawn up between Britain and France to carve up the Middle East after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. Britain, which had entered the war in 1914 outraged by German atrocities in Belgium and determined to uphold civilization and freedom from the German aggressor, had by 1916 adopted German methods of waging war with the ultimate goal of wholesale imperial expansion. En route however the purported ideals of the Empire had been fatally undermined.

It's instructive too, I think, to apply Soseki's analysis to the current situation in which Japan finds itself. While not a 'hot war' like the First World War, Japan is currently engaged in a major 'Cold War' with China, with each side viewing the other with profound suspicion and enmity. For some years now, a debate has raged in Japan about the need to revise the country's Peace Constitution, prohibiting the country from having a regular army, in order to adequately defend itself from the perceived Chinese threat.

These concerns are not to be dismissed, particularly in the light of an ever more assertive China and with the power of the US, Japan's protector, in seeming retreat. Many indeed argue that the Peace Constitution was an American imposition to start off with.

Yet to adopt Soseki's analysis, for Japan to change its very constitution in the light of a threat from China, is not a 'natural' development, but one forced upon it by China. In that sense, again to mimic Soseki, China could be thought to be 'winning'. As shown by Britain's experience in combatting Germany in the First World War, making such changes may succeed in their primary objective, but often have completely unforeseen, long-term consequences that can sow the seeds of one's own destruction.

On the occasion of the centennial anniversary of Ireland's 1916 Uprising, I think it's time to look again at the causes of it, not in a narrowly nationalistic light, but to trace its connections to events around the world and consider what insight those events might lend us to some highly pressing political issues in the world today.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)